On this week’s 51%, we hit the books. University of Virginia Professor Andrea Press explains how today’s media can better represent women in her book, Media-Ready Feminism and Everyday Sexism. And Dr. Sharon Ufberg speaks with Take the Lead’s Gloria Feldt about her latest title, Intentioning: Sex, Power, Pandemics, and How Women Will Take the Lead for Everyone’s Good.

Guests: Andrea Press, University of Virginia professor and co-author of Media-Ready Feminism and Everyday Sexism; Gloria Feldt, co-founder and president of Take the Lead and author of Intentioning: Sex, Power, Pandemics, and How Women Will Take the Lead for Everyone’s Good

51% is a national production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio. It’s produced by Jesse King, our executive producer is Dr. Alan Chartock, and our theme is “Lolita” by the Albany-based artist Girl Blue.

You’re listening to 51%, a WAMC production dedicated to women’s issues and experiences. Thanks for tuning in, I’m Jesse King.

We’ve got a pair of interviews with some fantastic authors today — and we’re going to start by getting a little meta and talking about the media. The media we consume can be a powerful thing: it can reflect the cultural and social norms of our time, make us feel heard and seen, and challenge society by exposing audiences to new ideas. So how is media faring when it comes to women? Well, if you ask our first guest, not too great — but it’s complicated in this digital age.

Andrea Press is a professor of media studies and sociology at the University of Virginia, and her new book with Francesca Tripodi — titled Media-Ready Feminism and Everyday Sexism: How U.S. Audiences Create Meaning Across Platforms — is out now on the State University of New York Press. In it, the pair explore how feminist messaging is blunted (or in some cases, created) in its consumption, and how media can better represent women of all backgrounds.

Press says the idea for the book started with an observation she and Tripodi made years ago.

“There was this pervasive idea in the culture that feminist activism had been successful and was finished, and there was not an ongoing problem. And that contradicted many experiences that women were having in their everyday lives,” Press explains. “And so, as sociologists, we were really interested in that disconnect between experience, and the way people understood their experience, and acted upon their experience. And as media scholars, we felt the media were playing an important role in this disconnect.

Just to start off at the beginning, what do you define as media-ready feminism?

Well, media-ready feminism was what we found when we examined the iteration of feminism in different media platforms. And the way we define media-ready feminism is a feminism that’s focused on the struggles of largely white, very affluent, successful women in the culture. It’s a version of feminism that kind of downplays the need for revolutionary change and sort of focuses on much more smaller reforms needed, but purports the idea that feminism is largely an accomplished goal. A good example of media-ready feminism would be the recent #Metoo movement, where we had a focus on the struggles of very glamorous, mostly white, affluent actresses – who did experience horrible instances of sexual harassment, and often sexual assault, at the hands of a very powerful and wealthy media producer Harvey Weinstein. It was still hard to get the story covered, and I don’t want to downplay the struggles the New York Times reporters and Ronan Farrow, who’s also very powerful and wealthy and a scion of Hollywood royalty, had to go through to get mainstream media to actually cover this story. It was hard. But it was impossible when the label “me too” was coined 11 years earlier by the African-American social worker Tarana Burke to talk about the struggles of her clients, who were distinctly less powerful, wealthy, and media-ready glamorous than the Hollywood actresses that we read so much about in the #Metoo movement. And that’s an example of how feminism needs to be media-ready to get into media coverage in mainstream media.

When a form of media or a particular message isn’t media-ready, how is it typically received by people? How does that back-and-forth usually go?

Well, we are scholars of the media audience, so it’s where sociology meets media, and we’re exactly interested in that moment where viewers and media users interpret what they’re seeing. There isn’t really one answer to that – we have instances in the book where women see through the sort of media-ready aspects of feminism presented in the media, and instances where they don’t. So for example, we have a chapter on work, family balance, and the way media represent that. And we talked about an episode of what was formerly a very popular show, Desperate Housewives, and about one of its characters, who had been a super successful advertising executive, who left her career to have four children. She has to go back to work because her husband loses his job. And it’s an interesting episode, because it talks about how hard it was to get the unemployed husband to step up and do childcare, and how difficult it was to get hired when she ended up having baby in tow at the interview, and what she experienced in the workplace being a very visible, working mother. And what we found in that chapter, when we interviewed older women who had been through very similar experiences, they really understood this as a structural problem, something that needed ongoing efforts and ongoing activism to address. And younger women, who had not been through these experiences themselves, sort of glossed over the issue and were not really able to identify this as an area where feminist activism and struggle was needed.

Tell me about some of the other forms of media that you looked at in this book, and some of your other findings here.

Well, we have a chapter on Game of Thrones, which we thought was very interesting text. You have queens and dragon rulers and, you know, very powerful women – who still were represented according to some of the norms of the way mainstream media often represents women: they were younger than you would expect a ruler to be, for example, they were highly sexualized in the way they were portrayed. And the norms of representing a sexual woman were very predictable according to mainstream media: they were most often white, they were most often blonde, they were most often thinner than the average woman. And so we were really interested in how audience members received these images. Did they focus on women’s power? Did they focus on stereotypical representations of women being highly sexualized? There was also a lot of sexual violence in that text. And we wondered if people noticed and found it disturbing, and sort of commented on it in their viewership. And we found both: people commented on how strong the women were, but tended, really not, for the most part, to notice the sexualization and the sexual violence, which even for mainstream television and film is pretty extreme. It is accepted by audience members because it is so pervasive in media representations to have women be highly sexualized, and to represent violence against women as a part of business as usual in our society.

Now, we’ve been speaking about shows that were created than offered to the public, but a lot of today’s media is also created within its audience. Can you talk a little bit about what you’ve been finding on that front, in terms of social media, and more just the way we engage with each other?

Well, we have two very interesting chapters in that regard. One is on Wikipedia, which, of course, is the people’s encyclopedia, created by the people. And you would imagine the norms of representation on Wikipedia to be egalitarian, but that is not what we found, and broader scholarship on Wikipedia has confirmed this. There actually is an under-representation, which is very systematic, of women and of people of color, of their achievements. Their standards of notability are much higher on Wikipedia, and repeated attempts to get notable women – and especially women of color – represented in that encyclopedia get torn down, they get deleted by the central core of editors that spends a lot of time deciding if people’s entries are legitimate or not. And we don’t have the answer to why this happens, but we do have a lot of data illustrating that it does happen, and it happens systematically. And of course, this has quite an impact on society, because we have armies of schoolchildren turning to Wikipedia to try to discover who is important in our culture, in our history. If women are not being included in this record, I think that is a very strong message we are sending our children, and it’s something we need to be aware of and probably take some steps to rectify. But that is continuing to happen.

We also looked at dating apps. We did as series of interviews with college students who use Tinder, and one of the things we found with Tinder is that there is an implicit agreement to sexual activity. There was a lot of to-do in Babe Magazine about a young woman who went on a date with a well-known celebrity, and there was this implicit idea that she was consenting to sexual activity by going on this date. And that is what we found to be an underlying norm of Tinder use – that there was an implicit consent assumed to sexual activity by both men and women going on Tinder dates. And we thought that was interesting. And the sexual assault epidemic on college campuses is not unrelated.

I thought that was a particularly like interesting part of the book as well, just because, with dating apps, they’re often spoken about as a way for women to take hold of their sexuality, or to have some sort of control over their relationships, and to have some choice there. But at the same time, a lot of people are interpreting swiping right as like, “You think I’m attractive. Done deal.”

Swipe right for assault is the name of our chapter.

So as you’re doing these studies, was there a particular part that connected with you, or that you were particularly surprised by?

I would say we were surprised by quite a bit of what we found in this book. And I go back to our original impetus for the book: I mean, we really didn’t understand why people did not identify the ongoing need for feminist activism and reform in the culture, and we felt it involved an ignoring of the experiences of everyday sexism – that women do confront sexual harassment, they confront discrimination, they confront an inordinate set of burdens when combining work and family that’s not shared by men in their lives. And what was keeping people from identifying this as gender inequality and identifying the need to change this kind of inequality. Seeing that the media do not present it as such, that they gloss over pervasive gender inequality, and they continually support the idea that feminism is no longer needed. That is something that we didn’t really expect to find so strongly across media platforms, but it added up to quite a system. And we felt like we were getting into the real inner workings of the way a patriarchy is reproduced. And that’s what we felt we found.

That kind of goes into one of my next questions. So if audience reaction plays a role in creating or changing the meaning of a piece, or even what goes out there, how can we better represent feminist ideas in media, and more accurately show these everyday sexisms?

Well, I think media producers – and it’s great to be in an interview here with a media producer – I think we all need to be including media producers much more conscious of the tendency to downplay the continuing need for struggle around gender equity. Because the data show that there is a continuing need for struggle around gender equity. There is harassment, there is assault, there is discrimination. There is a double standard. I didn’t talk about this, but we look at double standards around sexual activity, and the way it’s just assumed that women should engage in much less sexual activity than men – and they’re still called a series of names when they’re considered to be too highly sexual. And media need to really be committed to representing this data. I mean, it’s there. We know, we’re sociologists. It just doesn’t really get covered in a way that people pay attention to it.

I think the other much more pervasive issue, really, is that people need to not accept the way society is. And media play a big role in that. People need to understand that it is only through action and debate and activism that social change occurs. And we’ve seen vastly important social changes around issues of gender equity, around racial equity, around sexual discrimination and sexual equity because of the role activists have played in these issues. We see that we have an imperative to work to make our society better and more equitable. And people need to take that responsibility seriously. And I think the media can help this to happen.

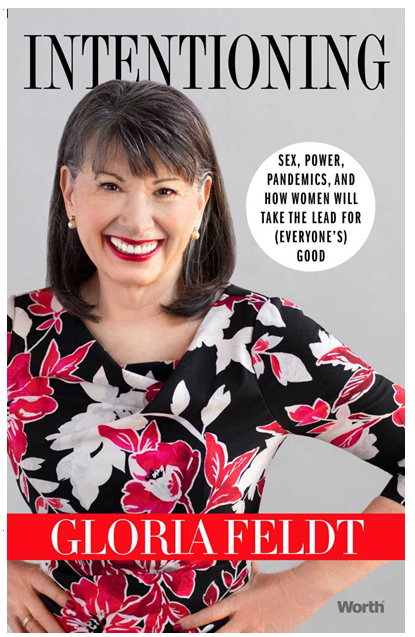

Gloria Feldt is the author of Intentioning: Sex, Power, Pandemics, and How Women Will Take the Lead for Everyone’s Good

Gloria Feldt is the author of Intentioning: Sex, Power, Pandemics, and How Women Will Take the Lead for Everyone’s GoodOur next guest is a New York Times bestselling author, a renowned speaker on women’s rights and leadership, and a former president and CEO of Planned Parenthood. Gloria Feldt is also the co-founder and president of Take the Lead, a nonprofit bringing leadership training to women and businesses with the mission of achieving leadership gender parity across all sectors by 2025. In her latest book, Intentioning: Sex, Power, Pandemics, and How Women Will Take the Lead for Everyone’s Good, Feldt shares the stories of various women during the COVID-19 pandemic to detail the power of intention, and offers her tips to help women reach their goals. She spoke with Dr. Sharon Ufberg, co-founder of the California-based personal development company, Borrowed Wisdom, for her 51% segment, “Force of Nature.”

How did Intentioning get started?

I had started writing Intentioning before the pandemic, and I knew that I wanted to build on my previous work, which focused on women’s relationship with power, and gave women leadership and power tools to thrive in the world as it is while changing it. I realized after I had been teaching from that book for almost 10 years, that once you have embraced your power, the next question that has to be asked is, “The power to what?” The power to what? And that’s where intention comes in. And I found that, because women have, often, an ambivalent relationship with power, and have to really claim power or learn the power that they have in their hands and their hearts and their minds – that often they don’t have the level of intentionality that boys and men are socialized to have. None of this is hardwired, by the way, I’m not saying men or women are better, or boys and girls are. But there are culturally learned traits that we have, and one of them is that we, as women, often don’t even hold up our hands and say we want that position, because a.) maybe we don’t see ourselves in it, and b.) we haven’t been taught to self-advocate as much. So once you know you have power, you have to ask, “The power to what?”

Now, I started writing the book by interviewing women, knowing that they would organically give me ideas for a new set of nine leadership tools, which indeed are in the book Intentioning. But when the pandemic came around, I also realized that I had to talk about the pandemics plural, as a social context within which we are all living right now: the pandemic of coronavirus and the pandemic of racial injustice that has been in this country forever, but we’ve finally started recognizing it on a larger basis. So the book then talks about the opportunity in disruption, the fact that disruption is also rebirth, that race and gender equality have to go forward together, and that traits we’ve learned as women that used to be things that set us back now can become our superpowers. And then I provide nine leadership and intentioning tools. So that’s the framework of the book as it ended up. Books write themselves eventually, you know.

You use inspiring individual women’s stories to discuss the important concepts and leadership tools in the book. Can you share one with us?

I’m going to share first, the story of Marina Arsenijevic. And Marina is a composer and a concert pianist. And the reason I want to share her story is it is such an amazing example of someone who could not practice her profession once the pandemic started. After all, a concert pianist can’t perform if you can’t go to where the people are. And instead of stepping back, she entered the most productive time of her professional life. She literally turned her house into a recording studio, she began to write music, more so than she had ever done before, because she had more time to do it. She began to, as she calls it, “I’m using my voice now,” so she’s singing in some of her music. She has actually acquired, gosh, like 600,000 Instagram followers. And millions, millions of people watch her music on YouTube now. So she has never been more productive, creating new music, recording music. She literally rethought – she didn’t change her purpose. In other words, her answer to the question of, “The power to what?” is still her music, but she found a completely different way to deliver it to the public.

I love the book, and it’s no surprise that my favorite leadership tool in the book is #7: be unreasonable. Can you tell us more about that one?

I take it, first of all, from one of my all-time favorite quotes, that stood me in good stead through most of my life as a leader. And it’s George Bernard Shaw, who said, “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world. The unreasonable one persists in trying to adopt the world to Himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” Now, he was a little bit of a feminist in his time, so I would sort of give him some slack and assume he would use “women” also, if he were saying that today. But I feel so much truth in that, so much reality in it. And some of the women that I profiled in this particular chapter are women like Charlotte George, who just took rejection after rejection after rejection, and turned it into two very profitable businesses. First, she co-founded Skagen, the watch company that’s now been bought by Fossil. I used to have five or six of those watches, because they were so beautiful and affordable at the same time. And then, after she sold Skagen – she actually had skin cancer a couple of times – and so because she’s outside a lot, she’s an equestrian, she created a new company called Castle Denmark that designs and creates sunscreen, beautiful sunscreen clothing that you can wear outside and protect your body from the sun. So Charlotte is one of those women who, I will tell you, it’s like she’s just a force of nature. It’s always about, “Well, what does the world need or want right now? I’m going to figure it out. And I’m going to do it, and I’m not going to adapt myself to the way it is.”

The other woman that I am in awe of, I have to tell you, is Rupa Dash. And I hadn’t ever heard of Rupa when she contacted me and asked me to speak at a conference that she put together at the Clinton Center in Little Rock, Arkansas, just a few months before everything shut down. So I’m glad I went – I was like, “Why would I go to Little Rock? It’s hard to even get there from anywhere.” – and I was blown away by how she had taken every one of the world’s biggest challenges, everything from food insecurity, to women’s rights, to the environment, and she had created what she called “her moonshot.” And she’s on a mission to engage all the women of the world in solving these problems. And never mind that people may say they’re unsolvable. She’s going to do it with her moonshots. I just know it, I feel it, it will happen.

Take the Lead has a goal of pay parity by 2025. Are we going to make that 2025 parity deadline? What’s the prognosis for making that goal?

That’s the big question right now, Sharon, but I believe we can do it, and I’ll tell you why. So we were clipping along at a nice pace. We had moved from 18 percent of the top leadership positions when I co-founded Take the Lead in 2013, to about 25 percent before the pandemic. Now most of the data says that women have been set back by 10 years as a result of the pandemic – but the way I see it is this: that in times of massive disruption, you also have massive opportunity for rebirth, rethinking and reconsidering things. And even old institutions have to be open to new ideas, because otherwise they will not survive. And we now can see that it’s perfectly possible for women and men to work from home if need be, to have flexible hours, to have flexible location, to be able to be more flexible in their work and be able to take care of their family responsibilities as well as their work responsibilities. These kinds of flexible accommodations have been asked for by women since we’ve been in the workforce in large numbers, and yet, our institutions have been very slow to adopt them. Well, now, they all know that it’s actually to their advantage [to adopt them], and in fact, if they want to bring these talented women that they have invested in back into their workforce, they’re going to have to have those flexibility opportunities, and they’re going to have to provide family leave, and they’re going to have to do many things that don’t actually hurt their business. In fact, it adds to their bottom line ultimately, but they’ve been very reluctant and unwilling to try. I actually see that in the next three years – if we do it now, things don’t just happen on their own, people have to make them happen – but if we gather together and we are absolutely committed to achieving gender parity by 2025, I believe we can still do it.

I love your optimism, and I do believe in these moments of great change, great leaps are possible. So where can people find you, Gloria, and where can they find your book?

People can get Intentioning at any of their favorite booksellers. You can find out more at my website, gloriafeldt.com. You can also find out about Take the Lead services, where we do training for individuals and companies, and also coaching, and provide many other kinds of programs and services at taketheleadwomen.com. I am a bit of a social media fiend, so people can always find me @gloriafeldt on any platform.

You’ve been listening to 51%. 51% is a national production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio. It’s produced by me, Jesse King. Our executive producer is Dr. Alan Chartock, and our theme is “Lolita” by the Albany-based artist Girl Blue. A big thanks to Andrea Press, Gloria Feldt, and Dr. Sharon Ufberg for taking part in this week’s episodes. Thanks to you for joining us this week — until next time, I’m Jesse King for 51%.

The federal government has approved billions of dollars in incentives for infrastructure and chip-manufacturing projects across the country. On this week’s 51%, we speak...

On this week’s 51%, we recognize Mother’s Day and the International Day of the Midwife. Betsy Mercogliano, a licensed midwife with Albany’s Family Life...

On this week’s 51%: we continue our series on women in business. Capital Region restaurateur Aneesa Waheed reflects on the success of her growing...